Should you be tested for inflammation?

Let’s face it: inflammation has a bad reputation. Much of it is well-deserved. After all, long-term inflammation contributes to chronic illnesses and deaths. If you just relied on headlines for health information, you might think that stamping out inflammation would eliminate cardiovascular disease, cancer, dementia, and perhaps aging itself.

Unfortunately, that’s not true.

Still, our understanding of how chronic inflammation can impair health has expanded dramatically in recent years. And with this understanding come three common questions: Could I have inflammation without knowing it? How can I find out if I do? Are there tests for inflammation? Indeed, there are.

Testing for inflammation

A number of well-established tests to detect inflammation are commonly used in medical care. But it’s important to note these tests can't distinguish between acute inflammation, which might develop with a cold, pneumonia, or an injury, and the more damaging chronic inflammation that may accompany diabetes, obesity, or an autoimmune disease, among other conditions. Understanding the difference between acute and chronic inflammation is important.

These are four of the most common tests for inflammation:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (sed rate or ESR). This test measures how fast red blood cells settle to the bottom of a vertical tube of blood. When inflammation is present the red blood cells fall faster, as higher amounts of proteins in the blood make those cells clump together. While ranges vary by lab, a normal result is typically 20 mm/hr or less, while a value over 100 mm/hr is quite high.

- C-reactive protein (CRP). This protein made in the liver tends to rise when inflammation is present. A normal value is less than 3 mg/L. A value over 3 mg/L is often used to identify an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, but bodywide inflammation can make CRP rise to 100 mg/L or more.

- Ferritin. This is a blood protein that reflects the amount of iron stored in the body. It’s most often ordered to evaluate whether an anemic person is iron-deficient, in which case ferritin levels are low. Or, if there is too much iron in the body, ferritin levels may be high. But ferritin levels also rise when inflammation is present. Normal results vary by lab and tend to be a bit higher in men, but a typical normal range is 20 to 200 mcg/L.

- Fibrinogen. While this protein is most commonly measured to evaluate the status of the blood clotting system, its levels tend to rise when inflammation is present. A normal fibrinogen level is 200 to 400 mg/dL.

Are tests for inflammation useful?

In certain situations, tests to measure inflammation can be quite helpful.

- Diagnosing an inflammatory condition. One example of this is a rare condition called giant cell arteritis, in which the ESR is nearly always elevated. If symptoms such as new, severe headache and jaw pain suggest that a person may have this disease, an elevated ESR can increase the suspicion that the disease is present, while a normal ESR argues against this diagnosis.

- Monitoring an inflammatory condition. When someone has rheumatoid arthritis, for example, ESR or CRP (or both tests) help determine how active the disease is and how well treatment is working.

None of these tests is perfect. Sometimes false negative results occur when inflammation actually is present. False positive results may occur when abnormal test results suggest inflammation even when none is present.

Should you be routinely tested for inflammation?

Currently, tests of inflammation are not a part of routine medical care for all adults, and expert guidelines do not recommend them.

CRP testing to assess cardiac risk is encouraged to help decide whether preventive treatment is appropriate for some people (such as those with a risk of a heart attack that is intermediate — that is, neither high nor low). However, for most people evidence suggests that routine CRP testing adds relatively little to assessment using standard risk factors, such as a history of hypertension, diabetes, smoking, high cholesterol, and positive family history of heart disease.

So far, only one group I know of recommends routine testing for inflammation for all without a specific reason: companies selling inflammation tests directly to consumers.

Inflammation may be silent — so why not test?

It’s true that chronic inflammation may not cause specific symptoms. But looking for evidence of inflammation through a blood test without any sense of why it might be there is much less helpful than having routine health care that screens for common causes of silent inflammation, including

- excess weight

- diabetes

- cardiovascular disease (including heart attacks and stroke)

- hepatitis C and other chronic infections

- autoimmune disease.

Standard medical evaluation for most of these conditions does not require testing for inflammation. And your medical team can recommend the right treatments if you do have one of these conditions.

The bottom line

Testing for inflammation has its place in medical evaluation, and in monitoring certain health conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis. But it’s not clearly helpful as a routine test for everyone. A better approach is to adopt healthy habits and get routine medical care that can identify and treat the conditions that contribute to harmful inflammation.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Robert H. Shmerling is the former clinical chief of the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and is a current member of the corresponding faculty in medicine at Harvard Medical School. … See Full Bio View all posts by Robert H. Shmerling, MD

Why all the buzz about inflammation — and just how bad is it?

Quick health quiz: how bad is inflammation for your body?

You’re forgiven if you think inflammation is very bad. News sources everywhere will tell you it contributes to the top causes of death worldwide. Heart disease, stroke, dementia, and cancer all have been linked to chronic inflammation. And that’s just the short list. So, what can you do to reduce inflammation in your body?

Good question! Before we get to the answers, though, let’s review what inflammation is — and isn’t.

Inflammation 101

Misconceptions abound about inflammation. One standard definition describes inflammation as the body’s response to an injury, allergy, or infection, causing redness, warmth, pain, swelling, and limitation of function. That’s right if we’re talking about a splinter in your finger, bacterial pneumonia, or the rash of poison ivy. But it’s only part of the story, because there’s more than one type of inflammation:

- Acute inflammation rears up suddenly, lasts days to weeks, and then settles down once the cause, such as an injury or infection, is under control. Generally, acute inflammation is a reaction that attempts to restore the health of the affected area. That’s the type described in the definition above.

- Chronic inflammation is quite different. It can develop for no medically apparent reason, last a lifetime, and cause harm rather than healing. This type of inflammation is often linked with chronic disease, such as:

-

- excess weight

- diabetes

- cardiovascular disease, including heart attacks and stroke

- certain infections, such as hepatitis C

- autoimmune disease

- cancer

- stress, whether psychological or physical.

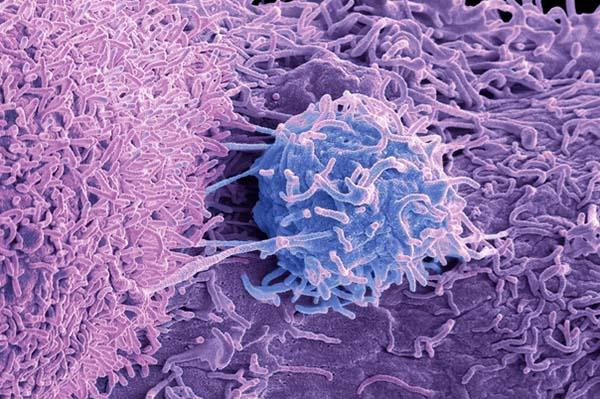

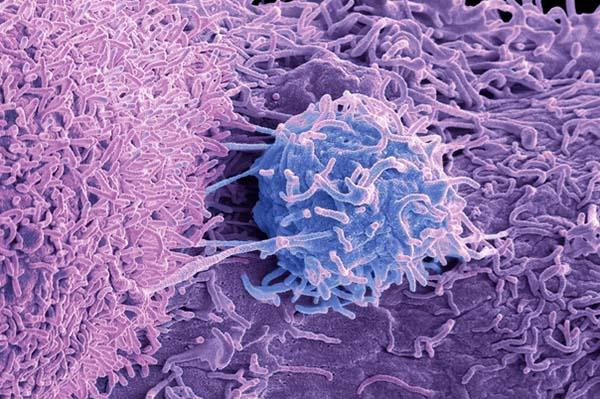

Which cells are involved in inflammation?

The cells involved with both types of inflammation are part of the body’s immune system. That makes sense, because the immune system defends the body from attacks of all kinds.

Depending on the duration, location, and cause of trouble, a variety of immune cells, such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages, rush in to create inflammation. Each type of cell has its own particular role to play, including attacking foreign invaders, creating antibodies, and removing dead cells.

4 inflammation myths and misconceptions

Inflammation is the root cause of most modern illness.

Not so fast. Yes, a number of chronic diseases are accompanied by inflammation. In many cases, controlling that inflammation is an important part of treatment. And it’s true that unchecked inflammation contributes to long-term health problems.

But inflammation is not the direct cause of most chronic diseases. For example, blood vessel inflammation occurs with atherosclerosis. Yet we don’t know whether chronic inflammation caused this, or whether the key contributors were standard risk factors (such as high cholesterol, diabetes, and smoking — all of which cause inflammation).

You know when you’re inflamed.

True for some conditions. People with rheumatoid arthritis, for example, know when their joints are inflamed because they experience more pain, swelling, and stiffness. But the type of inflammation seen in obesity, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease, for example, causes no specific symptoms. Sure, fatigue, brain fog, headaches, and other symptoms are sometimes attributed to inflammation. But plenty of people have those symptoms without inflammation.

Controlling chronic inflammation would eliminate most chronic disease.

Not so. Effective treatments typically target the cause of inflammation, rather than just suppressing inflammation itself. For example, a person with rheumatoid arthritis may take steroids or other anti-inflammatory medicines to reduce their symptoms. But to avoid permanent joint damage, they also take a medicine like methotrexate to treat the underlying condition that’s causing inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory diets or certain foods (blueberries! kale! garlic!) prevent disease by suppressing inflammation.

While it’s true that some foods and diets are healthier than others, it’s not clear their benefits are due to reducing inflammation. Switching from a typical Western diet to an “anti-inflammatory diet” (such as the Mediterranean diet) improves health in multiple ways. Reducing inflammation is just one of many possible mechanisms.

The bottom line

Inflammation isn’t a lone villain cutting short millions of lives each year. The truth is, even if you could completely eliminate inflammation — sorry, not possible — you wouldn’t want to. Among other problems, quashing inflammation would leave you unable to mount an effective response to infections, allergens, toxins or injuries.

Inflammation is complicated. Acute inflammation is your body’s natural, usually helpful response to injury, infection, or other dangers. But it sometimes sparks problems of its own or spins out of control. We need to better understand what causes inflammation and what prompts it to become chronic. Then we can treat an underlying cause, instead of assigning the blame for every illness to inflammation or hoping that eating individual foods will reduce it.

There’s no quick or simple fix for unhealthy inflammation. To reduce it, we need to detect, prevent, and treat its underlying causes. Yet there is good news. Most often, inflammation exists in your body for good reason and does what it’s supposed to do. And when it is causing trouble, you can take steps to improve the situation.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Robert H. Shmerling is the former clinical chief of the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and is a current member of the corresponding faculty in medicine at Harvard Medical School. … See Full Bio View all posts by Robert H. Shmerling, MD

Winter hiking: Magical or miserable?

By midwinter, our urge to hibernate can start to feel constricting instead of cozy. What better antidote to being cooped up indoors than a bracing hike in the crisp air outdoors?

Winter backdrops are stark, serene, and often stunning. With fewer people on the trail, you may spot more creatures out and about. And it’s a prime opportunity to engage with the seasons and our living planet around us, says Dr. Stuart Harris, chief of the Division of Wilderness Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. But a multi-mile trek through rough, frosty terrain is far different than warm-weather hiking, requiring consideration of health and safety, he notes. Here’s what to know before you go.

Winter hiking: Safety first

“The challenge of hiking when environmental conditions are a little more demanding requires a very different approach on a winter’s day as opposed to a summer’s day,” Dr. Harris says. “But it gives us a chance to be immersed in the living world around us. It’s our ancient heritage.”

A safety-first attitude is especially important if you’re hiking with others of different ages and abilities — say, with older relatives or small children. It’s crucial to have both the right gear and the right mindset to make it enjoyable and safe for all involved.

Planning and preparation for winter hikes

Prepare well beforehand, especially if you’re mixing participants with vastly different fitness levels. Plan your route carefully, rather than just winging it.

People at the extremes of age — the very old or very young — are most vulnerable to frigid temperatures, and cold-weather hiking can be more taxing on the body. “Winter conditions can be more demanding on the heart than a perfectly-temperatured day,” Harris says. “Be mindful of the physical capabilities of everyone in your group, letting this define where you go. It’s supposed to be fun, not a punishing activity.”

Before setting out:

- Know how far, high, and remote you’re going to go, Dr. Harris advises, and check the forecast for the area where you’ll be hiking, taking wind chill and speed into account. Particularly at higher altitudes, weather can change from hour to hour, so keep abreast of expectations for temperature levels and any precipitation.

- Know if you’ll have access to emergency cell coverage if anything goes wrong.

- Always share plans with someone not on your hike, including expected route and time you’ll return. Fill out trailhead registers so park rangers will also know you’re on the trail in case of emergency.

What to wear for winter hikes

Prepare for extremes of cold, wind, snow, and even rain to avoid frostbite or hypothermia, when body temperature drops dangerously low.

- Dress in layers. Several thin layers of clothing are better than one thick one. Peel off a layer when you’re feeling warm in high sun and add it back when in shadow. Ideally, wear a base layer made from wicking fabric that can draw sweat away from the skin, followed by layers that insulate and protect from wind and moisture. “As they say, there’s no bad weather, just inappropriate clothing,” Dr. Harris says. “Take a day pack or rucksack and throw a couple of extra thermal layers in. I never head out for any hike without some ability to change as the weather changes.”

- Protect head, hands, and feet. Wear a wool hat, a thick pair of gloves or mittens, and two pairs of socks. Bring dry spares. Your boots should be waterproof and have a rugged, grippy sole.

- Wear sunscreen. You can still get a sunburn in winter, especially in places where the sun’s glare reflects off the snow.

Carry essentials to help ensure safety

- Extra food and water. Hiking in the cold takes serious energy, burning many more calories than the same activity done in summer temperatures. Pack nutrient-dense snacks such as trail mix and granola bars, which often combine nuts, dried fruit, and oats to provide needed protein, fat, and calories. It’s also key to stay hydrated to keep your core temperature normal. Bonus points for bringing a warm drink in a thermos to warm your core if you’re chilled.

- First aid kit. Bandages for slips or scrapes on the trail and heat-reflecting blankets to cover someone showing signs of hypothermia are wise. Even in above-freezing temperatures, hypothermia is possible. Watch for signs such as shivering, confusion, exhaustion, or slurring words, and seek immediate help.

- Light source. Time your hike so you’re not on the trail in darkness. But bring a light source in case you get stuck. “A flashlight or headlamp is pretty darn useful if you’re hiking anywhere near the edges of daylight,” Harris says.

- Phone, map, compass, or GPS device plus extra batteries. Don’t rely on your phone for GPS tracking, but fully charge it in case you need to reach someone quickly. “Make sure that you have the technology and skill set to be able to navigate on- or off-trail,” Harris says, “and that you have a means of outside communication, especially if you’re in a large, mixed group.”

About the Author

Maureen Salamon, Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

Maureen Salamon is executive editor of Harvard Women’s Health Watch. She began her career as a newspaper reporter and later covered health and medicine for a wide variety of websites, magazines, and hospitals. Her work has … See Full Bio View all posts by Maureen Salamon

Let’s not call it cancer

Roughly one in six men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point in their lives, but these cancers usually aren’t life-threatening. Most newly diagnosed men have Grade Group 1 (GG1) prostate cancer, which can linger for years without causing significant harms.

Prostate cancer is categorized according to how far it has spread and how aggressive it looks under the microscope. Pure GG1 prostate cancer is the least risky form of the disease. It occurs frequently with age, will not metastasize to other parts of the body, and it doesn’t require any immediate treatment.

So, should we even call it cancer? Many experts say no.

Dr. Matthew Cooperberg, who chairs the department of urology at the University of California, San Francisco, says men wouldn’t suffer as much anxiety — and would be less inclined to pursue unneeded therapies — if their doctors stopped referring to low-grade changes in the prostate as cancer. He recently co-chaired a symposium where experts from around the world gathered to discuss the pros and cons of giving GG1 cancer another name.

Treatment discrepancies

GG1 cancer is typically revealed by PSA screening. The goal with screening is to find more aggressive prostate cancer while it’s still curable, yet these efforts often detect GG1 cancer incidentally. Attendees at the symposium agreed that GG1 disease should be managed with active surveillance. With this standard practice, doctors monitor the disease with periodic PSA checks, biopsies, and imaging, and treat the disease only if it shows signs of progression.

But even as medical groups work to promote active surveillance, 40% of men with low-risk prostate cancer in the United States are treated immediately. According to Dr. Cooperberg, that’s in part because the word “cancer” has such a strong emotional impact. “It resonates with people as something that spreads and kills,” he says. “No matter how much we try to get the message out there that GG1 cancer is not an immediate concern, there’s a lot of anxiety associated with a ‘C-word’ diagnosis.”

A consequence is widespread overtreatment, with tens of thousands of men needlessly suffering side effects from surgery or radiation every year. A cancer diagnosis has other harmful consequences: studies reveal negative effects on relationships and employment as well as “someone’s ability to get life insurance,” Dr. Cooperberg says. “It can affect health insurance rates.”

Debate about renaming

Experts at the symposium proposed that GG1 cancer could be referred to instead as acinar neoplasm, which is an abnormal but nonlethal growth in tissue. Skeptics expressed a concern that patients might not stick with active surveillance if they aren’t told they have cancer. But should men be scared into complying with appropriate monitoring? Dr. Cooperberg argues that patients with pure GG1 “should not be burdened with a cancer diagnosis that has zero capacity to harm them.”

Dr. Cooperberg does caution that since biopsies can potentially miss higher-grade cancer elsewhere in the prostate, monitoring the condition with active surveillance is crucial. Moreover, men with a strong family history of cancer, or genetic mutations such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 that put them at a higher risk of aggressive disease, should be followed more closely, he says.

Dr. Marc Garnick, the Gorman Brothers Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and editor in chief of the Harvard Medical School Guide to Prostate Diseases, agrees. Dr. Garnick emphasized that a name change for GG1 cancer needs to consider a wide spectrum of additional testing. “This decision can’t simply be based on pathology,” he says. “Biopsies only sample a miniscule portion of the prostate gland. Genetic and genomic tests can help us identify some low-risk cancers that might behave in a more aggressive fashion down the road.”

Meanwhile, support for a name change is gaining momentum. “Younger pathologists and urologists are especially likely to think this is a good idea,” Dr. Cooperberg says. “I think the name change is just a matter of time — in my view, we’ll get there eventually.”

About the Author

Charlie Schmidt, Editor, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases

Charlie Schmidt is an award-winning freelance science writer based in Portland, Maine. In addition to writing for Harvard Health Publishing, Charlie has written for Science magazine, the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Environmental Health Perspectives, … See Full Bio View all posts by Charlie Schmidt

About the Reviewer

Marc B. Garnick, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Marc B. Garnick is an internationally renowned expert in medical oncology and urologic cancer. A clinical professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, he also maintains an active clinical practice at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical … See Full Bio View all posts by Marc B. Garnick, MD

New surgery for benign prostate hyperplasia provides long-lasting benefits

Most men over 50 will develop an enlarged prostate. Also called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), this bothersome condition makes it hard to urinate and can eventually lead to other problems, such as infections, kidney stones, and bladder damage, if left untreated. Many different BPH therapies are available, including medications and various types of surgery.

One of the newer surgical options, called aquablation, trims excess prostate tissues with highly pressurized jets of saline. Doctors perform aquablation in the operating room while looking at the prostate gland on an ultrasound machine. Patients are put under general anesthesia, so they don’t feel any pain during the procedure.

Men typically have to urinate through a catheter for about 24 hours after surgery until swelling of the urethra (the tube through which urine flows out of the bladder) subsides. Aquablation is gaining in popularity — in part because, unlike other more traditional BPH treatments, it can preserve normal ejaculation.

In September, researchers published a study showing that improvements in urinary function from aquablation were still holding up after five years.

Results of data analysis

The study assessed long-term data from two clinical trials. The first, called the WATER trial (for Waterjet Ablation Therapy for Endoscopic Resection of Prostate Tissue) launched in 2015 and enrolled 116 men with prostates ranging up to 80 cubic centimeters. The second trial, WATER II, launched in 2017 and enrolled 101 men with prostates ranging between 80 and 150 cubic centimeters. (Normal prostates range from 25 to 30 cubic centimeters in size.) Enrolled patients had a median age of 66 in the WATER study and 68 in WATER II. In addition, 92% of men in the WATER trial were sexually active, as were 75% of the men in WATER II.

Both clinical trials used the so-called International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) to measure treatment-related improvements in urinary functioning and quality of life. Calculated based on how patients rate their symptoms on a standardized questionnaire, IPSS scores fall into three categories: mild symptom scores range from 1 to 7; intermediate symptom scores range from 8 to 18; and scores greater than 19 indicate severe symptoms.

When they first enrolled in the trials, men in the WATER and WATER II studies reported average IPSS scores of 22.9 and 23.3 respectively. Five years later, the average respective scores were much lower: 7.0 and 6.8. The average length of hospital stay was 1.4 days in the WATER group and 1.6 days for the WATER II group. Only 1% of men were taking BPH medications after five years, and fewer than 5% had been surgically re-treated.

Another randomized control trial, WATER III, is currently underway in Europe. That trial compares aquablation with a more established type of BPH surgery, prostate enucleation, which uses a laser to remove obstructing tissues. Six-month data reported in 2023 showed that men in either group had comparable symptom improvements.

However, 98% of men in the prostate enucleation group had ejaculatory dysfunction. That side effect is caused by damage to delicate tissues around the bladder neck that propel semen out of the body. Semen therefore flows back into the bladder, a condition called retrograde ejaculation. None of the men in the aquablation group reported ejaculatory problems.

A word of caution

Aquablation can result in extended bleeding, cautions Dr. Heidi Rayala, an assistant professor of urology at Harvard Medical School and a member of the Harvard Medical School Guide to Prostate Diseases advisory board. That’s because unlike other types of surgery for BPH, including prostate enucleation, aquablation doesn’t cauterize tissues with heat. “I tell my patients to expect some blood in the urine for about four to six weeks after the procedure,” Dr. Rayala said.

Moreover, aquablation may be unsuitable for some men who take blood thinners to prevent blood from clotting, according to Dr. Rayala. Appropriate candidates for the surgery must be able to “safely discontinue anticoagulant medications during post-operative healing, given the bleeding risk,” Dr. Rayala said. Still, aquablation is an excellent option for most men, Dr. Rayala said, especially those with medium to large prostates “who want a durable solution with a lower risk of sexual side effects.”

“These early results are encouraging, but limited by a relatively small number of patients,” said Dr. Marc Garnick, the Gorman Brothers Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and editor in chief of the Harvard Medical School Guide to Prostate Diseases. “Further evidence with a significantly larger number of patients and longer follow-up will help to support this new method of reducing prostate tissue as an important treatment option.”

About the Author

Charlie Schmidt, Editor, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases

Charlie Schmidt is an award-winning freelance science writer based in Portland, Maine. In addition to writing for Harvard Health Publishing, Charlie has written for Science magazine, the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Environmental Health Perspectives, … See Full Bio View all posts by Charlie Schmidt

About the Reviewer

Marc B. Garnick, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Marc B. Garnick is an internationally renowned expert in medical oncology and urologic cancer. A clinical professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, he also maintains an active clinical practice at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical … See Full Bio View all posts by Marc B. Garnick, MD

Flowers, chocolates, organ donation — are you in?

Chocolates and flowers are great gifts for Valentine’s Day. But what if the gifts we give then or throughout the year could be truly life-changing? A gift that could save a life or free someone from dialysis?

You can do this. For people in need of an organ, tissue, or blood donation, a donor can give them a gift that exceeds the value of anything that you can buy. Fittingly, Valentine’s Day is also known as National Donor Day, a time for blood drives and sign-ups for organ and tissue donation. Have you ever wondered what can be donated? Had reservations about donating after death or concerns about risks for live donors? Read on.

The enormous impact of organ, tissue, or cell donation

Imagine you have kidney failure requiring dialysis 12 or more hours each week just to stay alive. Even with this, you know you’re still likely to die a premature death. Or, if your liver is failing, you may experience severe nausea, itching, and confusion; death may only be a matter of weeks or months away. For those with cancer in need of a bone marrow transplant, or someone who’s lost their vision due to corneal disease, finding a donor may be their only good option.

Organ or tissue donation can turn these problems around, giving recipients a chance at a long life, a better quality of life, or both. And yet, the number of people who need organ donation far exceeds compatible donors. While national surveys have found about 90% of Americans support organ donation, only 40% have signed up. More than 103,000 women, men, and children are awaiting an organ transplant in the US. About 6,200 die each year, still waiting.

What can you donate?

The list of ways to help has grown dramatically. Some organs, tissues, or cells can be donated while you’re alive; other donations are only possible after death. A single donor can help more than 80 people!

After death, people can donate:

- bone, cartilage, and tendons

- corneas

- face and hands (though uncommon, they are among the newest additions to this list)

- kidneys

- liver

- lungs

- heart and heart valves

- stomach and intestine

- nerves

- pancreas

- skin

- arteries and veins.

Live donations may include:

- birth tissue, such as the placenta, umbilical cord, and amniotic fluid, which can be used to help heal skin wounds or ulcers and prevent infection

- blood cells, serum, or bone marrow

- a kidney

- part of a lung

- part of the intestine, liver, or pancreas.

To learn more about different types of organ donations, visit Donate Life America.

Becoming a donor after death: Questions and misconceptions

Common misconceptions about becoming an organ donor limit the number of people who are willing to sign up. For example, many people mistakenly believe that

- doctors won’t work as hard to save your life if you’re known to be an organ donor — or worse, doctors will harvest organs before death

- their religion forbids organ donation

- you cannot have an open-casket funeral if you donate your organs.

None of these is true, and none should discourage you from becoming an organ donor. Legitimate medical professionals always keep the patient’s interests front and center. Care would never be jeopardized due to a person’s choices around organ donation. Most major religions allow and support organ donation. If organ donation occurs after death, the clothed body will show no outward signs of organ donation, so an open-casket funeral is an option for organ donors.

Live donors: Blood, bone marrow, and organs

Have you ever donated blood? Congratulations, you’re a live donor! The risk for live donors varies depending on the intended donation, such as:

- Blood, platelets, or plasma: If you’re donating blood or blood products, there is little or no risk involved.

- Bone marrow: Donating bone marrow requires a minor surgical procedure. If general anesthesia is used, there is a chance of a reaction to the anesthesia. Bone marrow is removed through needles inserted into the back of the pelvis bones on each side. Back or hip pain is common, but can be controlled with pain relievers. The body quickly replaces the bone marrow removed, so no long-term problems are expected.

- Stem cells: Stem cells are found in bone marrow or umbilical cord blood. They also appear in small numbers in our blood and can be donated through a process similar to blood donation. This takes about seven or eight hours. Filgrastim, a medication that increases stem cell production, is given for a number of days beforehand. It can cause side effects such as flulike symptoms, bone pain, and fatigue, but these tend to resolve soon after the procedure.

- Kidney, lung, or liver: Surgery to donate a kidney or a portion of a lung or liver comes with a risk of complications, reactions to anesthesia, and significant recovery time. It’s no small matter to give a kidney, or part of a lung or liver.

The vast number of live organ donations occur without complications, and donors typically feel quite positive about the experience.

Who can donate?

Almost anyone can donate blood cells –– including stem cells –– or be a bone marrow, tissue, or organ donor. Exceptions include anyone with active cancer, widespread infection, or organs that aren’t healthy.

What about age? By itself, your age does not disqualify you from organ donation. In 2023, two out of five people donating organs were over 50. People in their 90s have donated organs upon their deaths and saved the lives of others.

However, bone marrow transplants may fail more often when the donor is older, so bone marrow donations by people over age 55 or 60 are usually avoided.

Finding a good match: Immune compatibility

For many transplants, the best results occur when there is immune compatibility between the donor and recipient. Compatibility is based largely on HLA typing, which analyzes genetically-determined proteins on the surface of most cells. These proteins help the immune system identify which cells qualify as foreign or self. Foreign cells trigger an immune attack; cells identified as self should not.

HLA typing can be done by a blood test or cheek swab. Close relatives tend to have the best HLA matches, but complete strangers may be a good match as well.

Fewer donors among people with certain HLA types make finding a match more challenging. Already existing health disparities, such as higher rates of kidney disease among Black Americans and communities of color, are worsened by lower numbers of donors from these communities, an inequity partly driven by a lack of trust in the medical system.

The bottom line

You can make an enormous impact by becoming a donor during your life or after death. In the US, you must opt in to be a donor after death. (Research suggests the opt-out approach many other countries use could significantly increase rates of organ donation in this country.)

I’m hopeful that organ donation in the US and throughout the world will increase over time. While you can still go with chocolates for Valentine’s Day, maybe this year you can also go bigger and become a donor.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Robert H. Shmerling is the former clinical chief of the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and is a current member of the corresponding faculty in medicine at Harvard Medical School. … See Full Bio View all posts by Robert H. Shmerling, MD

Beyond the usual suspects for healthy resolutions

Early in the new year, promises to reboot your health typically focus on diet, exercise, and weight loss. And by now you may have begun making changes — or at least plans — to reach those goals. But consider going beyond the big three.

Below are 10 often-overlooked, simple ideas to step up personal health and safety. And most won’t make you break a sweat.

Review your health portals

Your medical information is kept in electronic records. You have access to them through the patient portal associated with your doctor’s office. Set aside time to update portal passwords and peruse recent records of appointments, test results, and notes your doctor took during your visits.

“Many studies have shown that when patients review the notes, they remember far better what went on during interactions with their clinicians, take their medicines more effectively, and pick up on errors — whether it’s an appointment they forgot to make or something their doctor, nurse, or therapist got wrong in documenting an encounter,” says Dr. Tom Delbanco, the John F. Keane & Family Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and cofounder of the OpenNotes initiative, which led shared clinician notes to become the new standard of care.

Doing this can help you become more engaged in your care. “We know from numerous studies that engaged patients who share decisions with those caring for them have better outcomes,” he adds.

Ask about health insurance freebies

Your insurance plan may offer perks that can lead to better health, such as:

- weight loss cessation programs

- quit-smoking programs

- free or reduced gym memberships.

Some insurers even offer breastfeeding counseling and equipment. Call your insurance company or take a close look at their website to find out if there’s anything that would help you.

Get rid of expired medications

Scour your cabinets for expired or unneeded drugs, which pose dangers for you and others. Look for prescription and over-the-counter medications (pills, potions, creams, lotions, droppers, or aerosol cans) as well as supplements (vitamins, minerals, herbs).

Bring your finds to a drug take-back site, such as a drugstore or law enforcement office, or a medical waste collection site such as the local landfill.

As a last resort, toss medications into the trash, but only after mixing them with unappealing substances (such as cat litter or used coffee grounds) and placing the mixture in a sealable plastic bag or container.

Invest in new sneakers

The wrong equipment can sabotage any exercise routine, and for many people the culprit is a worn pair of sneakers. Inspect yours for holes, flattened arch support, and worn treads. New sneakers could motivate you to jazz up your walking or running routine.

For example, if it’s in the budget, buy a new pair of walking shoes with a wide toe box, cushy insoles, good arch support, a sturdy heel counter (the part that goes around your heel), stretchy uppers, and the right length — at least half an inch longer than your longest toe.

Cue up a new health app

There are more than 350,000 health apps geared toward consumer health. They can help you with everything from managing your medications or chronic disease to providing instruction and prompts for improving diet, sleep, or exercise routines, enhancing mental health, easing stress, practicing mindfulness, and more.

Hunt for apps that are free or offer a free trial period for a test drive. Look for good reviews, strong privacy guardrails, apps that don’t collect too much information from you, and those that are popular — with hundreds of thousands or millions of downloads.

Make a schedule for health screenings and visits

Is it time for a colonoscopy, mammogram, hearing test, prostate check, or comprehensive eye exam? Has it been a while since you had a dermatologist examine the skin on your whole body? Should you have a cholesterol test or other blood work — and when is a bone density test helpful?

If you’re not sure, call your primary care provider or any specialists on your health team to get answers.

Four more simple healthy steps

The list of steps you can take this year to benefit your health can be as long as you’d like it to be. Jot down goals any time you think of them.

Here are four solid steps to start you off:

- Take some deep breaths each day. A few minutes of daily slow, deep breathing can help lower your blood pressure and ease stress.

- Get a new pair of sunglasses if your old ones have worn lenses. Make sure the new pair has UV protection (a special coating) to block the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) light, which can cause eye damage and lead to permanent vision loss.

- Make a few lunch dates or phone dates with friends you haven’t seen in a while. Being socially connected wards off loneliness and isolation, which can help lower certain health risks.

- Do a deep cleaning on one room in your home per week. Dust and mold can trigger allergies, asthma, and even illness.

You don’t have to do all of these activities at once. Just put them on your to-do list, along with the larger resolutions you’re working on. Now you’ll have a curated list of goals of varying sizes. The more goals you reach, the better you’ll feel. And that will make for a very healthy year, indeed.

About the Author

Heidi Godman, Executive Editor, Harvard Health Letter

Heidi Godman is the executive editor of the Harvard Health Letter. Before coming to the Health Letter, she was an award-winning television news anchor and medical reporter for 25 years. Heidi was named a journalism fellow … See Full Bio View all posts by Heidi Godman

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Howard LeWine is a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing, and editor in chief of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. See Full Bio View all posts by Howard E. LeWine, MD

Should you be sleepmaxxing to boost health and happiness?

If you’ve been on TikTok lately, you know it’s hard to avoid countless influencers touting a concept called sleepmaxxing. Their posts provide tips and tricks to get longer, better, and more restorative sleep. And why not? Sleep is considered a pillar of good health and is related to everything from brain health to cardiovascular health, and even diabetes.

But what exactly is sleepmaxxing? And how likely is it to deliver on claims of amped-up energy, a boost to the immune system, reducing stress levels, and improving your mood?

What is sleepmaxxing?

Depending on which social media platform you happen to be looking at, the recommended strategies for maximizing sleep differ. Tips include:

- taping your mouth shut while sleeping

- not drinking anything during the two hours before bedtime

- a cold room temperature

- a dark bedroom

- using a white noise machine

- not setting a morning alarm

- showering one hour before bedtime

- eliminating caffeine

- eating kiwis before going to bed

- taking magnesium and melatonin

- using weighted blankets

- getting 30 minutes of sunlight every day

- meditating daily for 30 minutes.

Does any research support sleepmaxxing?

A thorough search through PubMed, PsycNet, and Google Scholar reveals zero results for the terms “sleepmaxx” and “sleepmaxxing.” But wait — this certainly doesn’t mean that some influencer-recommended strategies are not evidence-based, just that the concept of sleepmaxxing, as a defined package, has not been scientifically studied. But yes, some of the strategies — including one uncomfortable, though popular, choice — lack evidence.

Can mouth-taping improve your sleep?

TikTok users have claimed that taping your mouth while you sleep has benefits, such as reducing snoring and improving bad breath. A team from the department of otolaryngology at George Washington University was prompted by all of the social media buzz on the topic to review research on the impact of nocturnal mouth taping. Spoiler alert: the authors note that most TikTok mouth-taping claims aren’t supported by research.

If you do snore, it’s important to discuss this with your medical team. Even if taping your mouth reduces your snoring, it can’t effectively treat a potential underlying cause of the snoring, such as allergies, asthma, or sleep apnea.

Sleepmaxxing or basic sleep hygiene?

Many strategies recommended by sleepmaxxers are essentially what sleep experts prescribe as good sleep hygiene, which has plenty of research backing its value. Common components of sleep hygiene are decreasing caffeine and alcohol consumption, increasing physical activity, sleep timing, reducing evening light exposure, limiting daytime naps, and having a cool bedroom.

While tips like these help many people enjoy restful sleep, those who have an insomnia disorder will need more help, as described below.

Melatonin, early bedtime, weighted blankets, and — kiwi fruit?

Other strategies suggested by sleepmaxxers are based on limited scientific data. For example:

- Taking melatonin is recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine to treat circadian rhythm disorders such as jet lag. But it’s not recommended for insufficient sleep, poor sleep quality, or difficulty with falling asleep or staying asleep.

- Is it healthier to be asleep by 10 p.m.? One video that garnered more than a million views claims it is. While it is important to maximize morning sunlight exposure and minimize evening light exposure to regulate circadian rhythms, there is such variability in how much sleep someone requires and individual chronotypes (not to mention varying personal and professional responsibilities!) that it is difficult to state there is an ideal bedtime for everyone.

- While intriguing research has been done on weighted blankets, there is no convincing evidence that they are truly effective for the general adult population.

- Overall, it’s important to be cautious about the impact of the placebo effect on how someone sleeps. An analysis of more than 30 studies showed that roughly 64% of the drug response for a sleep medication in insomnia patients could be due to the placebo effect. A key takeaway is that studies that are not randomized controlled trials — such as this small study on 24 people suggesting that kiwi fruit may improve sleep — should be interpreted with a grain of salt.

Could you have orthosomnia?

The expectation of flawless sleep, night in and night out, is an unrealistic goal. Orthosomnia is a term that describes an unhealthy pursuit of perfect sleep. The pressure to get perfect sleep is embedded in the sleepmaxxing culture.

With more and more people able to access daily data about their sleep and other health metrics through consumer wearables, even a person who is objectively sleeping well can become unnecessarily concerned with optimizing their sleep. While prioritizing restful sleep is commendable, setting perfection as your goal is problematic. Even good sleepers vary from night to night, experiencing less than desirable sleep a couple of times per week.

It is also noteworthy that some of the most widely viewed recommendations on TikTok are not supported by scientific evidence.

Do you really need to fix your sleep?

A good first step is to understand whether or not there is anything that you need to fix! Consider tracking your sleep for a few weeks using a sleep diary, and pair this data with a consumer wearable (such as a Fitbit or Apple Watch). Both imperfectly capture sleep data when compared to the gold-standard tool sleep experts use (polysomnography, or a sleep study). However, combining the information can give you a reasonable assessment of your sleep status.

Regularly getting restful sleep can indeed boost health and mood. And all of us can benefit from following basic sleep hygiene tips. But if it takes you 30 minutes or more to fall asleep, or if you are up for 30 minutes or more in the middle of the night, and this happens three or more times per week, then consider reaching out to your health care team to seek further evaluation.

There are effective, nonmedication treatments that are proven to help you sleep better. One example is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, which can dramatically improve insomnia symptoms in a matter of weeks.

Want to learn more about cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia? Watch this video from the Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School with Eric Zhou describing how it works.

About the Author

Eric Zhou, PhD, Contributor

Eric Zhou, PhD, is an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He has been invited to speak internationally about sleep health in both pediatric and adult populations, including those with chronic illnesses. His research … See Full Bio View all posts by Eric Zhou, PhD

Life can be challenging: Build your own resilience plan

Nantucket, a beautiful, 14-mile-long island off the coast of Massachusetts, has a 40-point resiliency plan to help withstand the buffeting seas surrounding it as climate change takes a toll. Perhaps we can all benefit from creating individual resilience plans to help handle the big and small issues that erode our sense of well-being. But what is resilience and how do you cultivate it?

What is resilience?

Resilience is a psychological response that helps you adapt to life’s difficulties and seek a path forward through challenges.

“It’s a flexible mindset that helps you adapt, think critically, and stay focused on your values and what matters most,” says Luana Marques, an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

While everyone has the ability to be resilient, your capacity for resilience can take a beating over time from chronic stress, perhaps from financial instability or staying in a job you dislike. The longer you’re in that situation, the harder it becomes to cope with it.

Fortunately, it’s possible to cultivate resilience. To do so, it helps to exercise resiliency skills as often as possible, even for minor stressors. Marques recommends the following strategies.

Shift your thoughts

In stressful situations, try to balance out your thoughts by adopting a broader perspective. “This will help you stop using the emotional part of your brain and start using the thinking part of your brain. For example, if you’re asking for a raise and your brain says you won’t get it, think about the things you’ve done in your job that are worthy of a raise. You’ll slow down the emotional response and shift your mindset from anxious to action,” Marques says.

Approach what you want

“When you’re anxious, stressed, or burned out, you tend to avoid things that make you uncomfortable. That can make you feel stuck,” Marques says. “What you need to do is get out of your comfort zone and take a step toward the thing you want, in spite of fear.”

For example: If you’re afraid of giving a presentation, create a PowerPoint and practice it with colleagues. If you’re having conflict at home, don’t walk away from your partner — schedule time to talk about what’s making you upset.

Align actions with your values

“Stress happens when your actions are not aligned with your values — the things that matter most to you or bring you joy. For example, you might feel stressed if you care most about your family but can’t be there for dinner, or care most about your health but drink a lot,” Marques says.

She suggests that you identify your top three values and make sure your daily actions align with them. If being with family is one of the three, make your time with them a priority — perhaps find a way to join them for a daily meal. If you get joy from a clean house, make daily tidying a priority.

Tips for success

Practice the shift, approach, and align strategies throughout the week. “One trick I use is looking at my calendar on Sunday and checking if my actions for the week are aligned with my values. If they aren’t, I try to change things around,” Marques says.

It’s also important to live as healthy a lifestyle as possible, which will help keep your brain functioning at its best.

Healthy lifestyle habits include:

- getting seven to nine hours of sleep per night

- following a healthy diet, such as a Mediterranean-style diet

- aiming for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activities (such as brisk walking) each week — and adding on strength training at least twice a week

- if you drink alcohol, limiting yourself to no more than one drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men

- not smoking

- staying socially connected, whether in person, by phone or video calls, social media, or even text messages.

Need resilience training?

Even the best athletes have coaches, and you might benefit from resilience training.

Consider taking an online course, such as this one developed by Luana Marques. Or maybe turn to a therapist online or in person for help. Look for someone who specializes in cognitive behavioral therapy, which guides you to redirect negative thoughts to positive or productive ones.

Just don’t put off building resilience. Practicing as you face day-to-day stresses will help you learn skills to help navigate when dark clouds roll in and seas get rough.

About the Author

Heidi Godman, Executive Editor, Harvard Health Letter

Heidi Godman is the executive editor of the Harvard Health Letter. Before coming to the Health Letter, she was an award-winning television news anchor and medical reporter for 25 years. Heidi was named a journalism fellow … See Full Bio View all posts by Heidi Godman

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Howard LeWine is a practicing internist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Chief Medical Editor at Harvard Health Publishing, and editor in chief of Harvard Men’s Health Watch. See Full Bio View all posts by Howard E. LeWine, MD

Measles is making a comeback: Can we stop it?

Has the recent news about measles outbreaks in the US surprised you? Didn’t it seem like we were done with measles?

In the US, widespread vaccination halted the ongoing spread of measles more than 20 years ago, a major public health achievement. Before an effective vaccine was developed in the 1960s, nearly every child in the US got measles. Complications like measles-related pneumonia or hearing loss were common, and 400 to 500 people died each year.

As I write this, there have been 800 confirmed cases in 24 states, mostly among children. The biggest outbreak is in west Texas, where 62 people have been hospitalized and two unvaccinated school-age children recently died, the first measles deaths in the US since 2015. Officials in New Mexico have also reported a measles-related death.

Can we prevent these tragedies?

Measles outbreaks are highly preventable. It’s estimated that when 95% of people in a community are vaccinated, both those individuals and others in their community are protected against measles.

But nationally, measles vaccination rates among school-age kids fell from 95% in 2019 to 92% in 2023. Within Texas, the kindergarten vaccination rates have dipped below 95% in about half of all state counties. In the community at the center of the west Texas outbreak, the reported rate is 82%. Declining vaccination rates are common in other parts of the US, too, and that leaves many people vulnerable to measles infections.

Only 2% of the recent cases in the US involved people known to be fully vaccinated. The rest were either unvaccinated or had unknown vaccine status (96%), or they had received only one of the two vaccine doses (1%).

What to know about measles

As measles outbreaks occur within more communities, it’s important to understand why this happens — and how to stop it. Here are seven things to know about measles.

The measles virus is highly contagious

Several communities have suffered outbreaks in recent years. The measles virus readily spreads from person to person through the air we breathe. It can linger in the air for hours after a sneeze or cough. Estimates suggest nine out of 10 nonimmune people exposed to measles will become infected. Measles is far more contagious than the flu, COVID-19, or even Ebola.

Early diagnosis is challenging

It usually takes seven to 14 days for symptoms to show up once a person gets infected. Common early symptoms — fever, cough, runny nose — are similar to other viral infections such as colds or flu. A few days into the illness, painless, tiny white spots in the mouth (called Koplik spots) appear. But they’re easy to miss, and are absent in many cases. A day or two later, a distinctive skin rash develops.

Unfortunately, a person with measles is highly contagious for days before the Koplik spots or skin rash appear. Very often, others have been exposed by the time measles is diagnosed and precautions are taken.

Measles can be serious and even fatal

Measles is not just another cold. A host of complications can develop, including

- brain inflammation (encephalitis), which can lead to seizures, hearing loss, or intellectual disability

- pneumonia

- eye inflammation (and occasionally, vision loss)

- poor pregnancy outcomes, such as miscarriage

- subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a rare and lethal disease of the brain that can develop years after the initial measles infection.

Complications are most common among children under age 5, adults over age 20, pregnant women, and people with an impaired immune system. Measles is fatal in up to three of every 1,000 cases.

During the latest outbreaks, 85 cases —nearly one in nine — have required hospitalization.

Getting measles may suppress your immune system

When you get sick from a viral or bacterial infection, antibodies created by your immune system will later recognize and help mount a defense against these intruders. In 2019, a study at Harvard Medical School (HMS) found that the measles virus may wipe out up to three-quarters of antibodies protecting against viruses or bacteria that a child was previously immune to — anything from strains of the flu to herpesvirus to bacteria that cause pneumonia and skin infections.

“If your child gets the measles and then gets pneumonia two years later, you wouldn’t necessarily tie the two together. The symptoms of measles itself may be only the tip of the iceberg,” said the study’s first author, Dr. Michael Mina, who was a postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of geneticist Stephen Elledge at HMS and Brigham and Women’s Hospital at the time of the study.

In this video, Mina and Elledge discuss their findings.

Vaccination is highly effective

Two doses of the current vaccine provide 97% protection — much higher than most other vaccines. Rarely, a person gets measles despite being fully vaccinated. When that happens, the disease tends to be milder and less likely to spread to others.

The measles vaccine is safe

The safety profile of the measles vaccine is excellent. Common side effects include temporary soreness in the arm, low-grade fever, and muscle pain, as is true for most vaccinations. A suggestion that measles or other vaccines cause autism has been convincingly discredited. However, this often-repeated misinformation has contributed to significant vaccine hesitancy and falling rates of vaccination.

Ways to protect yourself from measles infection

- Vaccination. Usually, children are given the first dose around age 1 and the second between ages 4 and 6 as part of the Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) vaccine. If a child — or adult — hasn’t been vaccinated, they can have these doses later.

If you were born after 1957 and received a measles vaccination before 1968, consider getting revaccinated or tested for measles antibodies (see below). The vaccine given before 1968 was less effective than later versions. And before 1957, most people became immune after having measles, although this immunity can wane.

- Isolation. To limit spread, everyone diagnosed with measles and anyone who might be infected should avoid close contact with others until four days after the rash resolves.

- Mask-wearing by people with measles can help prevent spread to others. Household members or other close contacts should also wear a mask to avoid getting it.

- Frequent handwashing helps keep the virus from spreading.

- Testing. If you aren’t sure about your measles vaccination history or whether you may be vulnerable to infection, consider having a blood test to find out if you’re immune to measles. Memories about past vaccinations can be unreliable, especially if decades have gone by, and immunity can wane.

- Pre-travel planning. If you are headed to a place where measles is common, make sure you are up to date with vaccinations.

The bottom line

While news about measles in recent months may have been a surprise, it’s also alarming. Experts warn that the number of cases (and possibly deaths) are likely to increase. And due to falling vaccination rates, outbreaks are bound to keep occurring. One study estimates that between nine and 15 million children in the US could be susceptible to measles.

But there’s also good news: we know that measles outbreaks can be contained and the disease itself can be eliminated. Learn how to protect yourself and your family. Engage respectfully with people who are vaccine hesitant: share what you’ve learned from reliable sources about the disease, especially about the well-established safety of vaccination.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Dr. Robert H. Shmerling is the former clinical chief of the division of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), and is a current member of the corresponding faculty in medicine at Harvard Medical School. … See Full Bio View all posts by Robert H. Shmerling, MD